TINA.org Continues to Support FTC Efforts to Prohibit Junk Fees

TINA.org comment showcases the ongoing need for an FTC rule.

Some California consumers were miffed after dining at Hilton San Diego Resort & Spa restaurants and finding out – after they finished eating and drinking – that the restaurants had charged them more than the prices shown on the menus. According to the fine print at the bottom of the menus, Hilton San Diego restaurants — all owned by Noble House Hotels & Resorts — add a 3.5 percent surcharge to all dining bills “to help cover increasing labor costs and in our support of the recent increases in minimum wage and benefits for our dedicated team members.” In other words, a surcharge to help Noble House bring home more bacon.

Feeling robbed of their ability to make an informed decision prior to ordering and eating, the consumers filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of California against Noble House alleging it had engaged in false and misleading advertising by not featuring the true price next to each dish. But, in an interesting decision, the judge assigned to the case determined that the consumers’ lawsuit did not hold water because menus are not ads.

To arrive at this conclusion, the Court looked at a California state statute (which explains that ads include “shelf tags, displays and media advertising,” such as “newspapers, magazines, broadcast stations, billboards and transit ads”), and to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (which defines an ad as “a public notice,” especially “one published in the press or broadcast over the air”). The court said:

Restaurant menus are not public announcements which are published or disseminated to the general public in an effort to arouse a desire to buy or patronize; rather, they are lists of offerings of items available at a restaurant.

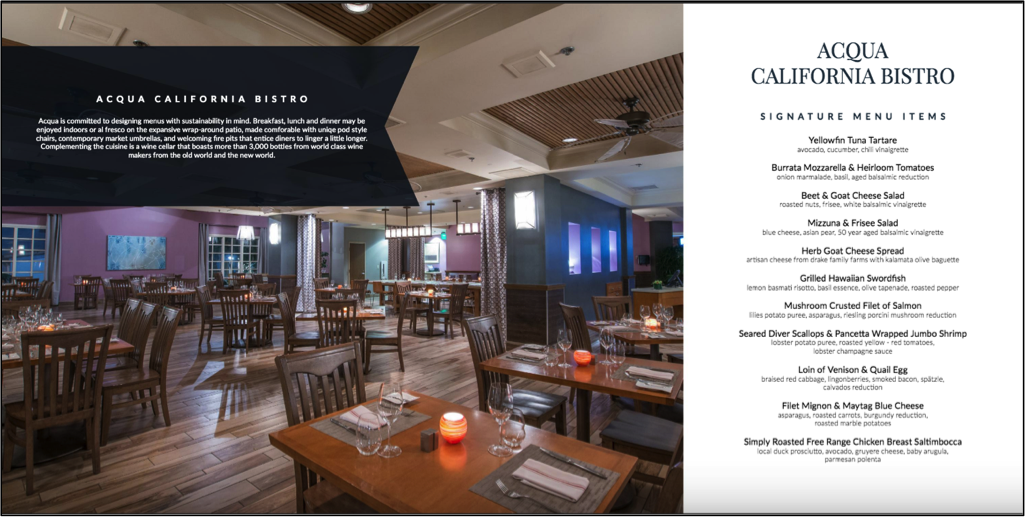

Yes, menus are indeed lists of restaurant offerings. But can’t they also be used to “arouse a desire to buy”? Before you answer that question, take a look at this Noble House promotional brochure for Hilton San Diego. Here’s a closer look at the second page of the brochure:

Hey, look at that. A menu. And judging by the caption on the photo (“Acqua is committed to designing menus with sustainability in mind. Breakfast, lunch and dinner may be enjoyed indoors or al fresco on the expansive wrap-around patio, made comfortable with unique pod style chairs, contemporary market umbrellas, and welcoming fire pits that entice diners to linger a little longer…”), it seems like Noble House is trying to “arouse a desire to buy.”

Which is exactly what restaurants like McDonald’s and Arby’s are doing when they feature parts of their menus in national television commercials:

In fact, if menus weren’t used to arouse a desire to buy, then these things — frequently placed outside restaurants for passersby to see — wouldn’t exist:

Websites and professional consultants who advise restaurant clients on how to write and use menus as marketing tools wouldn’t exist either. (Neither would phrases like “truffle essence” or “European style butter” but that’s beside the point.)

And as one professor of menus (yes, it’s an academic field too) explained, “the way a menu is laid out can determine whether you make it or break it. A restaurant has to manipulate people into buying particular items. It’s an important part of the profit.”

So now back to the original question: Can menus be used to arouse a desire to buy? By now, the answer should be a piece of cake. Hopefully, the next court that has to answer this question thinks so too.

TINA.org comment showcases the ongoing need for an FTC rule.

TINA.org applauds proposed rulemaking and recommends addition.

First, e-liquids. Now, THC edibles. Will energy drinks be next?