When TINA.org Investigations Collide

These brand collabs are far from fab.

Study demonstrates that effectively designed native advertising disclosures can decrease consumer deception.

| Michelle A. Amazeen

In November, scholars and practitioners from around the world gathered at the University of East London for the Branded Content Research Network conference. Among the many panels was one called, “Is there anything wrong with branded content?” One category of branded content drew much consternation: native advertising. Particularly in a news media environment, critics are concerned about the consistency of disclosure labels that are supposed to identify the content as advertising and the ability of audiences to recognize it as such.

What is Native Advertising?

Native advertising closely resembles the content surrounding it, often being indistinguishable except for a small disclosure label that is supposed to be present. In social media feeds, a native ad looks like a Facebook post or Tweet from a friend with a small disclosure labeling it as “Sponsored” or “Promoted.” On the websites of news organizations, a native ad looks like a news article that a journalist would post, often right down to the same typeface. Although the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – the governmental regulator in the U.S. that oversees fair business practices – requires clear and conspicuous disclosure of commercial content, there is no consistency in how online publishers label native advertising.

Some news organizations use language such as “sponsored content” or “paid advertising” to label the native advertising hosted on their site. However, many news sites use ambiguous terms such as “partner content,” “in association with,” or “brought to you by…” As reported during a recent FTC workshop on native advertising, many people do not understand what this type of language means. Beyond the ambiguous language, the lack of standardization only adds to the confusion of audiences.

Critics have also noted that to appease advertisers, some publishers make disclosures harder to see. For instance, both Twitter and the New York Times have been called out for toning down the visual prominence of their labeling on sponsored content.

Do People Recognize Native Advertising?

The close resemblance to news content and the lack of disclosure clarity and standardization has made it difficult for audiences to recognize when they are seeing an advertisement. A growing number of academic studies demonstrate that typically fewer than one in four people are able to identify a native ad in a digital news context. Most recently, a study I published with Bart Wojdynski from the University of Georgia showed that less than 10 percent of readers recognized as commercial in nature an article on a news website with a disclosure identifying it as native advertising. While this study was based upon a representative sample of 800 U.S. residents, it is likely that effects would be comparable wherever native advertising is used in Western democracies with similar advertising-supported media systems.

One of the things we were interested in measuring was whether certain types of disclosures are more effective than others. To do this, we manipulated three attributes of the disclosures in our experiment: 1) the explicitness of the language used, 2) the visual prominence of the disclosure, and 3) whether or not a sponsor’s logo was present. The least explicit version of our disclosure used the term “partner content.” The moderate version read “sponsored content,” and the most explicit version was “paid advertisement from [name of sponsor].” We had two versions of visual prominence with the less prominent using a 10 point “ghosted” gray font and the more prominent in a larger, heavier font highlighted with a red box. Participants in our experiment were randomly assigned to one of the various combinations of how the disclosure looked (see below).

Low versus High Native Advertising Disclosure Prominence

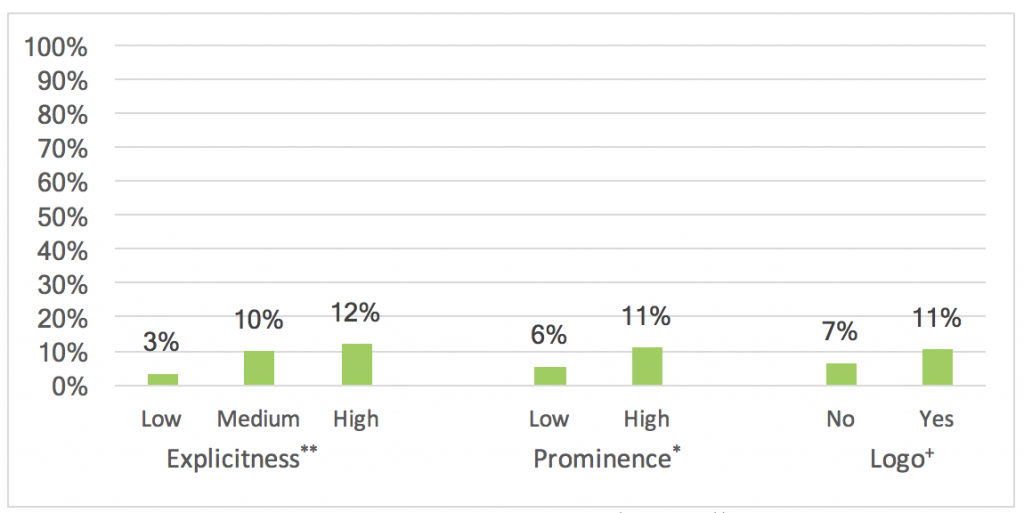

As expected, we found that people were significantly more likely to recognize native advertising when disclosures used explicit language in a visually prominent format (see below). Using a sponsor’s logo may help a little, too. Furthermore, not only is the disclosure format important, but so is its placement. In another study, Wojdynski found that the location of a disclosure on a web page also affects recognition. People were most likely to notice disclosures that were in the middle of a page rather than at the top – where most disclosures are currently positioned.

Native Advertising Recognition by Disclosure Characteristics

How Do People Feel About Native Advertising?

Although some “studies” report that consumers enjoy native advertising, these are typically industry-sponsored studies that ask survey respondents this question directly. To avoid having participants in our studies tell us what they think we might like to hear, we used indirect measures for our news and media consumption study. Specifically, we found that when people recognized what they were seeing as advertising, their evaluations of the publisher that hosted the ad were negatively affected. They had less favorable attitudes toward the publisher and found them less credible compared to people who did not recognize the content as native advertising.

What these results mean for news publishers is that although native advertising offers them incremental revenue in an industry where advertising income (both print and digital) has declined steeply, it may come at a cost to their brand reputations. And these results are based upon a single exposure to a native advertisement. It’s quite possible that repeated exposure to native advertising on news media websites could have even more detrimental effects.

Media critics and even some of our study participants point out that the lack of transparency in the use of native advertising by news organizations is particularly problematic in this era of “fake news.” By blurring the lines between what is editorial content and commercial content, publishers contribute to what Mara Einstein refers to as “content confusion” in her book, Black Ops Advertising, or what Ira Basen has called an “undifferentiated content swamp.” The less audiences are able to distinguish between real news and what’s not real news, the more likely fake news purveyors are able to establish a presence in our media ecosystem. As I have written elsewhere, that proverbial horse has already left the barn. Between 2014 and 2016, the number of fake news stories per month increased by over 1,000 percent.

With this new research on how audiences perceive branded news stories and which type of disclosure characteristics best enable native advertising recognition, policy makers and publishers who are serious about clearing up content confusion now have the evidence to make informed decisions.

These brand collabs are far from fab.

And why the problem is even worse when those human viewers are kids.

TINA.org Executive Director Bonnie Patten to speak at FTC workshop Wednesday.