Court Rules that Success by Health Was a Pyramid Scheme

Court also finds that defendants made false and deceptive earnings claims.

The financial appeal of multi-level marketing companies attracts investors and swindlers alike.

| William Keep, Ph.D.

Much ink has been spilled attacking and defending the MLM model and the associated risk of operating a product-based pyramid scheme—topics most analysts, investors, and journalists knew little about before 2013. Many comments continue to demonstrate a shallow understanding of the key issues.

Businesses need revenue to survive. (For a terrific book on this process I recommend “The External Control of Organizations.”) Marketing and/or a sales force are typically charged with revenue generation and used in different combinations by different businesses. Some businesses have relied, in part or in full, on a sales force that sells directly to consumers (i.e., direct selling). In the 1920s direct selling became popular in the United States for products ranging from food and cosmetics to furniture, musical instruments, and even automobiles. Selling costs for the parent firm included the cost of regularly replacing a percent of the sales force each year. The percentage varied from firm to firm and year to year.

By the mid-20th century the MLM approach began to grow. This business model reduced the parent firm’s selling cost by shifting recruitment and training onto the sales force itself (more on this below) and thereby creating the possibility of turning what was previously a cost into an important new source of revenue. In other words, the process of successfully recruiting new salespeople could, in and of itself, generate significant profits for the parent firm. The approach proved so successful that during the1980s when decades old, traditional, single-level direct selling companies with established brands struggled, new MLM companies thrived—two direct selling approaches operating in the same economy and facing the same social changes.

With the MLM approach, recruits purchase products not only for demonstration purposes and personal use, as could be true in single-level direct selling, but they are also incentivized by the “business opportunity” to make continuing purchases to meet volume targets to be eligible to earn rewards through recruiting others. Thus, the MLM approach creates two potential revenue sources for the parent firm that are both dependent upon purchases made by recruits. The first follows from products resold to consumers outside of the sales network (hereafter referred to as consumer demand) and the second obtained from products that never leave the sales network. The margin to the parent firm is the same in either case, creating financial ambivalence and even indifference as to the presence or absence of consumer demand.

MLM companies found to be pyramid schemes—either through a successful prosecution or an unwillingness to mount a defense—have relied primarily on only one revenue source, purchases made by recruits that do not result in sales to consumers outside of the sales network. With little or no documented consumer demand, the sales network itself provides the induced demand for the product. The BurnLounge court observed that “rewards BurnLounge paid for package sales were not tied to the consumer demand for the merchandise in the packages.” This language is consistent with the district court’s observation that “such sales were not driven by market forces.” So, what do legal, direct selling companies have that pyramid schemes do not have? Established and verifiable consumer demand independent of the sales network.

Now back to the issue of selection. The total lack of selection in the recruitment process represents another important difference between traditional direct selling and the MLM approach. When the parent firms bears the cost of recruiting and training, prudent selection becomes key to developing an effective sales force. Purchases by consumers outside of the sales network provide tangible proof of the benefits of thoughtfully selecting the sales force. Unproductive salespeople do not make money for themselves or for the parent company.

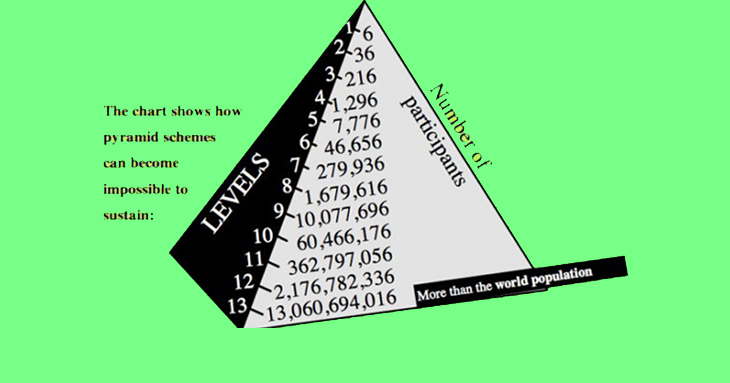

In the MLM model, selection in the recruitment process can actually inhibit product sales and related profits because EVERY POTENTIAL RECRUIT REPRESENTS POTENTIAL PROFIT. Purchases by the sales force, rather than by consumers outside of the sales network, now represents a key financial measure. While products purchased by the sales force can be resold to consumers outside of the sales network, doing so provides no additional financial return for the parent company. Not surprisingly, MLM companies historically report a large percentage of recruits who quickly become inactive, having no apparent sales to consumers outside the sales network and no longer purchasing products for themselves. As a result, successful attraction and even a churning of recruits can become the focus of the organization, an inherent risk of a model that can readily turn the MLM into a pyramid scheme—intentionally or not.

Ironically, the MLM model turns the selling role on its head. Successful selling, particularly business-to-consumer selling, is typically portrayed as challenging, requiring a particular skill set. Yet with the MLM approach, by and large, recruitment equals sales. The equation holds regardless of what happens to the product, further eliciting marketing messages to suggest that anyone can succeed. To illustrate the point, examples of successful MLM salespeople with no previous sales experience are prominently displayed. While some percentage of people with no sales experience have unrealized selling skills, the examples of success do not include the paths that led to success. In other words, an incentive and compensation structure where success hinges on recruiting others and not on selling to consumers outside of the sales network simply deepens the risk of an MLM company being a pyramid scheme. To sustain the requisite recruitment, MLM companies found to be pyramid schemes are concomitantly found to resort to fraud and misrepresentations.

The financial appeal of MLM companies attracts investors and swindlers alike. The appeal comes from the two revenue sources and the outsized gross margins. MLM companies report gross margins well above typical consumer products companies. Where Herbalife and Nu Skin, for example, report gross margins in the 80% range, Proctor & Gamble reports closer to 50%. Avon, a traditional direct selling company that added but never fully embraced an MLM approach in the 1990s, reports in the 60% range. Recruits serve as buyer and seller—a context that necessarily justifies product prices to facilitate the recruitment of others. The appropriateness of the product price becomes part of the marketing message. A buyer’s inclination to be price sensitive is transformed into a seller’s inclination to justify the price, since the success of the recruit hinges on the ability to sell the proposed opportunity to others. Oversized gross margin attracts all sorts of attention, sometimes even the attention of regulators.

The BurnLounge court noted the lack of “consumer demand” in finding the company to be a pyramid scheme rather than a legal MLM company, thereby guiding regulators to return to the original purpose of direct selling to the consumer. The lack of product purchases outside of the sales network, ambivalence toward the sources of margin, recruitment without selection (i.e., anyone can succeed), and examples of success unrelated to consumer demand will continue to plague this industry until addressed by regulators.

Margin used to compensate for recruitment and associated purchases, combined with a well-documented churning of recruits, should be red flags to regulators as to the economic purpose and viability of the company. A company’s share price provides no useful information as to presence or absence of fraud, and investors (long or short) are generally not responsible for assessing the legality of an MLM company. Even Milton Friedman saw that shareholder benefits should come “so long as it (the company) stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” The time has come for regulators to articulate the rules of the game in the MLM industry.

The views, opinions, and positions expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, and positions of TINA.org.

Court also finds that defendants made false and deceptive earnings claims.

A recap of TINA.org pressuring Nerium to #GetReal

Watch for #NeriumTruth social media campaign exposing company’s inappropriate health and income claims.